Content note: This post contains personal reflections on being outed, emotional manipulation, and mental health. Please take care while reading. Names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals involved.

I once gave an artist talk to just five people. One of them even admitted they were there by accident, but they stayed and listened. The five attendees sat in an awkward line across from me, as I delivered my thoughts alone from the other end of the gallery. It was only days after the Christchurch mosque attacks, and the city still felt smashed apart. I wasn’t sure if it was tactless to hold any sort of event while everything was so raw, but the show was already hung, and I felt obligated to the gallery and to those I’d already invited. I still don’t know if it was the right thing to do, or if there was a right thing to do.

Maybe it was the small audience, or maybe it was how disturbed I was feeling at the time but, that day, I spoke more honestly about myself and my art than I ever had before. I definitely overshared. But I didn’t regret it afterwards. If anything, it’s more often my silence that I regret, not the times I said too much.

So, when I was diagnosed as neurodivergent earlier this year, I told pretty much everyone.

This might not be the wisest strategy for someone working in high-stakes fields where privacy is essential, but I’ve accepted that I’m not that person. I’m ineluctably an artist who works best in isolation and I don’t care who knows. Coming out might feel redundant to some. For me, it’s become a form of reclamation and something I feel I have to do.

When I was 17, in my final year at high-school, there was no Grindr, and no smartphones for that matter. But there was NZDating, and it was my private window into the LGBTQIA+ world. I used it daily, and would chat to almost anyone from the safety of the family desktop computer. From there, I even started seeing an older guy, Adrian, who lived close enough that I could visit him after school when I didn’t have sports or rehearsal. He seemed harmless. We’d pick tomatoes and fresh basil from his garden and make sandwiches for afternoon tea. We’d do other things, too.

I wasn’t out. Not to anyone. At the time, I didn’t know a single openly gay student at school. Even my closest school friend, Sebastian, who had graduated the year before, didn’t know this about me, but I had my suspicions about him, and I figured we would come out to each other eventually, when we were ready. At the time “gay” was the most popular pejorative in school, and I got the sense that it wasn’t something to be proud of.

After a few months I ended things with Adrian. Maybe it was getting too intense, or maybe I just wasn’t ready. Either way, he didn’t take it at all well. Over the course of one long, surreal day, I was approached by my family, my friends, and even coworkers, all of whom had received calls from someone telling them I was gay.

Adrian had decided my discretion was a problem, and his solution was to out me to everyone. Maybe he thought it would bring us closer. Maybe he just wanted to regain control. Either way, I felt exposed and I didn’t know what to do or who to turn to for help.

So I called Sebastian, the one person who felt safe. I went to his flat, the place I usually felt most myself, and I let it all out. I told him I was gay, that I’d been seeing someone I met online, and that the breakup had spiraled out of control.

Sebastian listened. He smiled a kind of smug, mischievous smile I didn’t quite understand. And then he told me he already knew. He and Adrian had been talking. In fact, they had become quite fond of each other. And then he opened the door and Adrian walked in. They were together now. And they both seemed to find my panic quite amusing…

…It took me years to fully name what happened that day. At the time, I convinced myself it wasn’t betrayal and that maybe this was just what people were like. Maybe this was friendship. I buried my feelings and continued to try and be a good friend to Sebastian for many years. He was quite persuasive.

Years later, to my embarrassment, I let him down professionally while working as his photographer- and he turned on me completely. Even now, almost 20 years later, I hear of instances where he’s tried to discredit me, subtly or otherwise. The truth is, even after my coming-out turmoil, I still wanted to be a good friend to Sebastian, so I tried to do the work he wanted from me, even though I didn’t have the right equipment or, probably, the skills. These days I’ll admit, I’m not a particularly good photographer but I have always tried to be for friends when they’ve needed one.

So now, coming out is not about visibility for me. It’s about authorship. It’s about reclaiming control over my story, especially when so much of my life was shaped by concealing myself and my needs, or being revealed by others before I was ready. Being outed as gay taught me what it felt like to be seen on someone else’s terms. Coming out as neurodivergent, very recently, offered a way to see myself on my own terms.

Before seeking professional diagnosis for ADHD and Autism (or Audhd, as they’re sometimes called, in combination), my energy was constantly diminished, and I had become fearful of basic social interactions with even my favourite friends and family. I had begun to suspect I had ADHD, due to ongoing executive dysfunction, but I couldn’t explain how I had gone from loving performing arts to generally fearing being seen at all. It turns out that a ‘fear of being perceived’ is a documented neurodivergent experience. I’ll let neurosparkhealth.com put it better than I can:

“The fear of being perceived, which can also be described as the fear of “being seen,” is a particularly intense experience for many neurodivergent people. Whether autistic, ADHD, or otherwise neurodivergent, individuals who experience this fear often feel hyperaware of how they are viewed by others. This anxiety can be exacerbated by societal expectations and the pressure to conform to neurotypical norms, which can lead to masking, emotional exhaustion, and self-doubt.”

For years I thought I was just being professional, adaptable, considerate, when I was actually curating a version of myself that wouldn’t get rejected. And not just socially but artistically too. I used to take unsolicited criticism as a cue to vanish and reappear elsewhere, usually with a new medium or in a quieter shape. I got used to editing my voice into something more palatable.

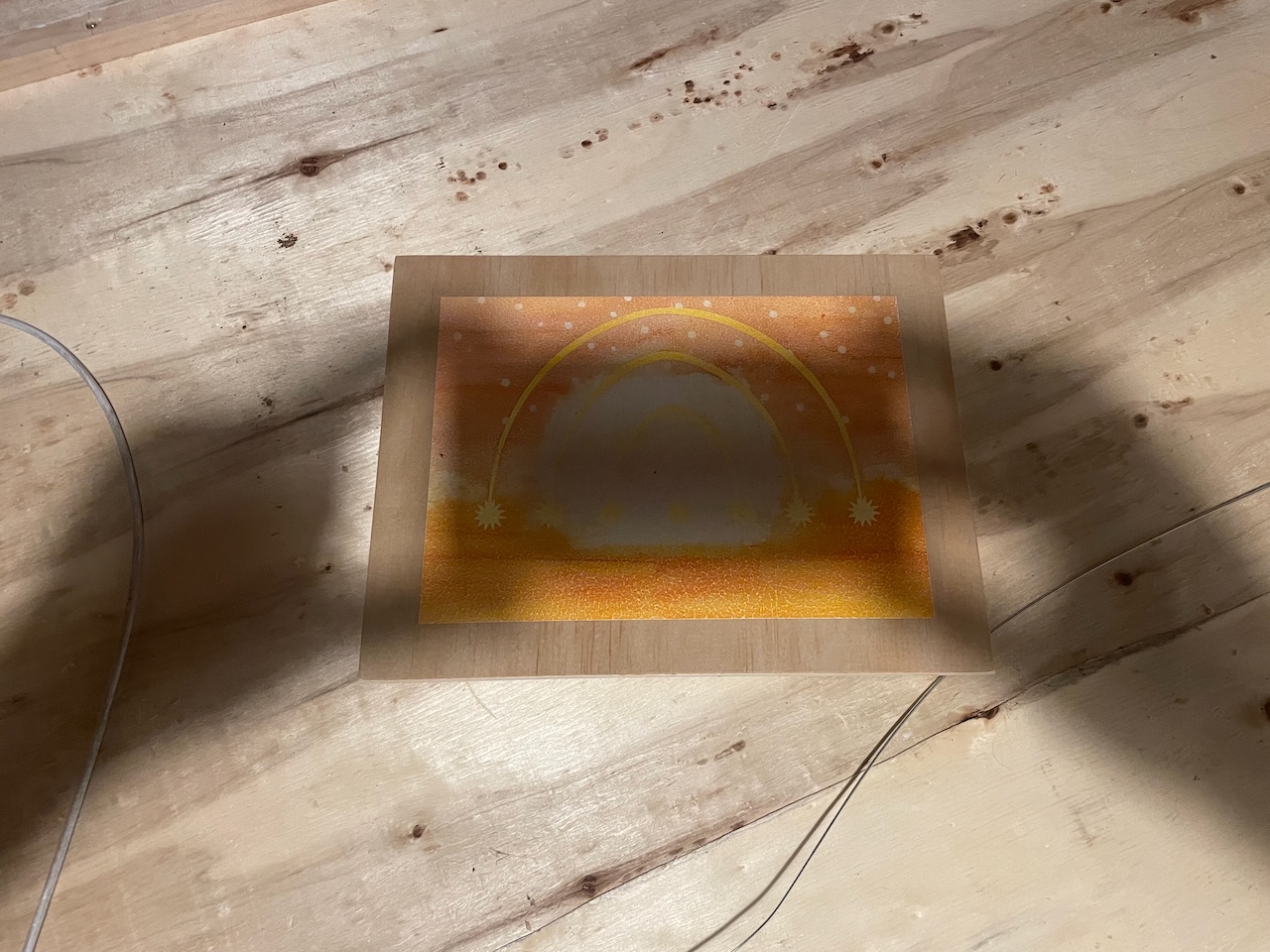

These days, I’m returning to making the art that feels inevitable to me. I try to let the work hold complexity and, for now, It doesn’t need to be immaculate. It doesn’t need to win anyone over. It just needs to be mine.

If I don’t make the artworks I need to make, no one else will.

And if I don’t tell my story as I experience it, who else will?

Thanks for reading -Ed

If you are struggling with issues related to mental health, identity, or being outed, you can find support through:

- OutLine Aotearoa — 0800 688 5463 or outline.org.nz

- Rainbow Youth — ry.org.nz

- Neurodivergent Empowerment Network NZ — neonnz.org

- 1737 — Free text or call 1737 in New Zealand to talk to a trained counsellor

Leave a Reply